Full-Text Search is one of those tools people use every day without realizing it. If you ever googled "golang coverage report" or tried to find "indoor wireless camera" on an e-commerce website, you used some kind of full-text search.

Full-Text Search (FTS) is a technique for searching text in a collection of documents. A document can refer to a web page, a newspaper article, an email message, or any structured text.

Today we are going to build our own FTS engine. By the end of this post, we'll be able to search across millions of documents in less than a millisecond. We'll start with simple search queries like "give me all documents that contain the word cat " and we'll extend the engine to support more sophisticated boolean queries.

Note

Most well-known FTS engine is Lucene (as well as Elasticsearch and Solr built on top of it).

Before we start writing code, you may ask "can't we just use grep or have a loop that checks if every document contains the word I'm looking for?". Yes, we can. However, it's not always the best idea.

We are going to search a part of the abstract of English Wikipedia. The latest dump is available at dumps.wikimedia.org . As of today, the file size after decompression is 913 MB. The XML file contains over 600K documents.

Document example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kit-Cat_Klock The Kit-Cat Klock is an art deco novelty wall clock shaped like a grinning cat with cartoon eyes that swivel in time with its pendulum tail.

First, we need to load all the documents from the dump. The built-in encoding/xml package comes very handy:

import (

"encoding/xml"

"os"

)

type document struct {

Title string `xml:"title"`

URL string `xml:"url"`

Text string `xml:"abstract"`

ID int

}

func loadDocuments(path string) ([]document, error) {

f, err := os.Open(path)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

defer f.Close()

dec := xml.NewDecoder(f)

dump := struct {

Documents []document `xml:"doc"`

}{}

if err := dec.Decode(&dump); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

docs := dump.Documents

for i := range docs {

docs[i].ID = i

}

return docs, nil

}

Every loaded document gets assigned a unique identifier. To keep things simple, the first loaded document gets assigned ID=0, the second ID=1 and so on.

Now that we have all documents loaded into memory, we can try to find the ones about cats. At first, let's loop through all documents and check if they contain the substring cat :

func search(docs []document, term string) []document {

var r []document

for _, doc := range docs {

if strings.Contains(doc.Text, term) {

r = append(r, doc)

}

}

return r

}

On my laptop, the search phase takes 103ms - not too bad. If you spot check a few documents from the output, you may notice that the function matches caterpillar and category , but doesn't match Cat with the capital C . That's not quite what I was looking for.

We need to fix two things before moving forward:

Make the search case-insensitive (so Cat matches as well).

Match on a word boundary rather than on a substring (so caterpillar and communication don't match).

One solution that quickly comes to mind and allows implementing both requirements is regular expressions .

Here it is - (?i)\bcat\b :

(?i) makes the regex case-insensitive

\b matches a word boundary (position where one side is a word character and another side is not a word character)

func search(docs []document, term string) []document {

re := regexp.MustCompile(`(?i)\b` + term + `\b`) // Don't do this in production, it's a security risk. term needs to be sanitized.

var r []document

for _, doc := range docs {

if re.MatchString(doc.Text) {

r = append(r, doc)

}

}

return r

}

Ugh, the search took more than 2 seconds. As you can see, things started getting slow even with 600K documents. While the approach is easy to implement, it doesn't scale well. As the dataset grows larger, we need to scan more and more documents. The time complexity of this algorithm is linear - the number of documents required to scan is equal to the total number of documents. If we had 6M documents instead of 600K, the search would take 20 seconds. We need to do better than that.

To make search queries faster, we'll preprocess the text and build an index in advance.

The core of FTS is a data structure called Inverted Index . The Inverted Index associates every word in documents with documents that contain the word.

Example:

documents = {

1: "a donut on a glass plate",

2: "only the donut",

3: "listen to the drum machine",

}

index = {

"a": [1],

"donut": [1, 2],

"on": [1],

"glass": [1],

"plate": [1],

"only": [2],

"the": [2, 3],

"listen": [3],

"to": [3],

"drum": [3],

"machine": [3],

}

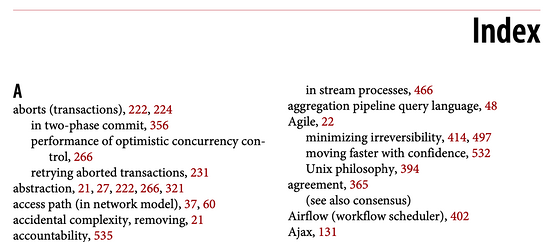

Below is a real-world example of the Inverted Index. An index in a book where a term references a page number:

Before we start building the index, we need to break the raw text down into a list of words (tokens) suitable for indexing and searching.

The text analyzer consists of a tokenizer and multiple filters.

The tokenizer is the first step of text analysis. Its job is to convert text into a list of tokens. Our implementation splits the text on a word boundary and removes punctuation marks:

func tokenize(text string) []string {

return strings.FieldsFunc(text, func(r rune) bool {

// Split on any character that is not a letter or a number.

return !unicode.IsLetter(r) && !unicode.IsNumber(r)

})

}

> tokenize("A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts.")

["A", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "Only", "the", "donuts"]

In most cases, just converting text into a list of tokens is not enough. To make the text easier to index and search, we'll need to do additional normalization.

In order to make the search case-insensitive, the lowercase filter converts tokens to lower case. cAt , Cat and caT are normalized to cat . Later, when we query the index, we'll lower case the search terms as well. This will make the search term cAt match the text Cat .

func lowercaseFilter(tokens []string) []string {

r := make([]string, len(tokens))

for i, token := range tokens {

r[i] = strings.ToLower(token)

}

return r

}

> lowercaseFilter([]string{"A", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "Only", "the", "donuts"})

["a", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "only", "the", "donuts"]

Almost any English text contains commonly used words like a , I , the or be . Such words are called stop words . We are going to remove them since almost any document would match the stop words.

There is no "official" list of stop words. Let's exclude the top 10 by the OEC rank . Feel free to add more:

var stopwords = map[string]struct{}{ // I wish Go had built-in sets.

"a": {}, "and": {}, "be": {}, "have": {}, "i": {},

"in": {}, "of": {}, "that": {}, "the": {}, "to": {},

}

func stopwordFilter(tokens []string) []string {

r := make([]string, 0, len(tokens))

for _, token := range tokens {

if _, ok := stopwords[token]; !ok {

r = append(r, token)

}

}

return r

}

> stopwordFilter([]string{"a", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "only", "the", "donuts"})

["donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donuts"]

Because of the grammar rules, documents may include different forms of the same word. Stemming reduces words into their base form. For example, fishing , fished and fisher may be reduced to the base form (stem) fish .

Implementing a stemmer is a non-trivial task, it's not covered in this post. We'll take one of the existing modules:

import snowballeng "github.com/kljensen/snowball/english"

func stemmerFilter(tokens []string) []string {

r := make([]string, len(tokens))

for i, token := range tokens {

r[i] = snowballeng.Stem(token, false)

}

return r

}

> stemmerFilter([]string{"donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donuts"})

["donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donut"]

Note

A stem is not always a valid word. For example, some stemmers may reduce airline to airlin .

func analyze(text string) []string {

tokens := tokenize(text)

tokens = lowercaseFilter(tokens)

tokens = stopwordFilter(tokens)

tokens = stemmerFilter(tokens)

return tokens

}

The tokenizer and filters convert sentences into a list of tokens:

> analyze("A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts.")

["donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donut"]

The tokens are ready for indexing.

Back to the inverted index. It maps every word in documents to document IDs. The built-in map is a good candidate for storing the mapping. The key in the map is a token (string) and the value is a list of document IDs:

type index map[string][]int

Building the index consists of analyzing the documents and adding their IDs to the map:

func (idx index) add(docs []document) {

for _, doc := range docs {

for _, token := range analyze(doc.Text) {

if ids != nil && ids[len(ids)-1] == doc.ID {

// Don't add same ID twice.

continue

}

idx[token] = append(idx[token], doc.ID)

}

}

}

func main() {

idx := make(index)

idx.add([]document{{ID: 1, Text: "A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts."}})

idx.add([]document{{ID: 2, Text: "donut is a donut"}})

fmt.Println(idx)

}

It works! Each token in the map refers to IDs of the documents that contain the token:

map[donut:[1 2] glass:[1] is:[2] on:[1] only:[1] plate:[1]]

To query the index, we are going to apply the same tokenizer and filters we used for indexing:

func (idx index) search(text string) [][]int {

var r [][]int

for _, token := range analyze(text) {

if ids, ok := idx[token]; ok {

r = append(r, ids)

}

}

return r

}

> idx.search("Small wild cat")

[[24, 173, 303, ...], [98, 173, 765, ...], [[24, 51, 173, ...]]

And finally, we can find all documents that mention cats. Searching 600K documents took less than a millisecond (18µs)!

With the inverted index, the time complexity of the search query is linear to the number of search tokens. In the example query above, other than analyzing the input text, search had to perform only three map lookups.

The query from the previous section returned a disjoined list of documents for each token. What we normally expect to find when we type small wild cat in a search box is a list of results that contain small , wild and cat at the same time. The next step is to compute the set intersection between the lists. This way we'll get a list of documents matching all tokens.

Luckily, IDs in our inverted index are inserted in ascending order. Since the IDs are sorted, it's possible to compute the intersection between two lists in linear time. The intersection function iterates two lists simultaneously and collect IDs that exist in both:

func intersection(a []int, b []int) []int {

maxLen := len(a)

if len(b) > maxLen {

maxLen = len(b)

}

r := make([]int, 0, maxLen)

var i, j int

for i b[j] {

j++

} else {

r = append(r, a[i])

i++

j++

}

}

return r

}

Updated search analyzes the given query text, lookups tokens and computes the set intersection between lists of IDs:

func (idx index) search(text string) []int {

var r []int

for _, token := range analyze(text) {

if ids, ok := idx[token]; ok {

if r == nil {

r = ids

} else {

r = intersection(r, ids)

}

} else {

// Token doesn't exist.

return nil

}

}

return r

}

The Wikipedia dump contains only two documents that match small , wild and cat at the same time:

> idx.search("Small wild cat")

130764 The wildcat is a species complex comprising two small wild cat species, the European wildcat (Felis silvestris) and the African wildcat (F. lybica).

131692 Catopuma is a genus containing two Asian small wild cat species, the Asian golden cat (C. temminckii) and the bay cat.

The search is working as expected!

By the way, this is the first time I hear about catopuma , here is one of them:

We just built a Full-Text Search engine. Despite its simplicity, it can be a solid foundation for more advanced projects.

I didn't touch on a lot of things that can significantly improve the performance and make the engine more user friendly. Here are some ideas for further improvements:

Persist the index to disk. Rebuilding it on every application restart may take a while.

Extend boolean queries to support OR and NOT .

Experiment with memory and CPU-efficient data formats for storing sets of document IDs. Take a look at Roaring Bitmaps .

Support indexing multiple document fields.

Sort results by relevance.

The full source code is available on GitHub .

以上就是本文的全部内容,希望对大家的学习有所帮助,也希望大家多多支持 我们

京公网安备 11010802041100号 | 京ICP备19059560号-4 | PHP1.CN 第一PHP社区 版权所有

京公网安备 11010802041100号 | 京ICP备19059560号-4 | PHP1.CN 第一PHP社区 版权所有